ChatGPT and the Planning Fallacy

How tech might slow you down

I am chronically late. I wasn’t always this way—I was known as the punctual friend for a long time—but I’ve found it harder and harder to get to things exactly when intended as time goes on.

This was a mystery to me for a while. I always felt that I planned things well—if I just finished work at 5:15, left at 5:30, got to the gym at 5:45, then picked up my fiancée at 6:45, we could get where we needed to be at 7 no problem. Of course, in practice, that never quite worked—I would lose five minutes on every one of those, little tasks, and that left us 20 minutes behind without anything major going wrong.

I was a victim of what’s sometimes called the planning fallacy. It’s often defined as our tendency to underestimate our future challenges. We don’t think enough about the time needed or the costs taken to get something done. It’s been observed in academia (students often underestimate how long their research projects will take by at least a month), industry, and, of course, everyday life.

I’d like to propose a different version of the same definition. I think the planning fallacy is a tendency to get caught up in the best-case scenarios and ignore what’s happening in practice. We think of how perfectly everything could go without considering all the places it could go wrong.

Of course, familiarity eventually sets in. You’ll realize over time what’s realistic. It’s easy to make the same mistake twice, though making the same mistake a few dozen times tends to teach you a lesson.

But what about when we don’t even realize that we’re making a mistake? What happens when we can’t recognize our shortcomings?

Invisible Obstacles

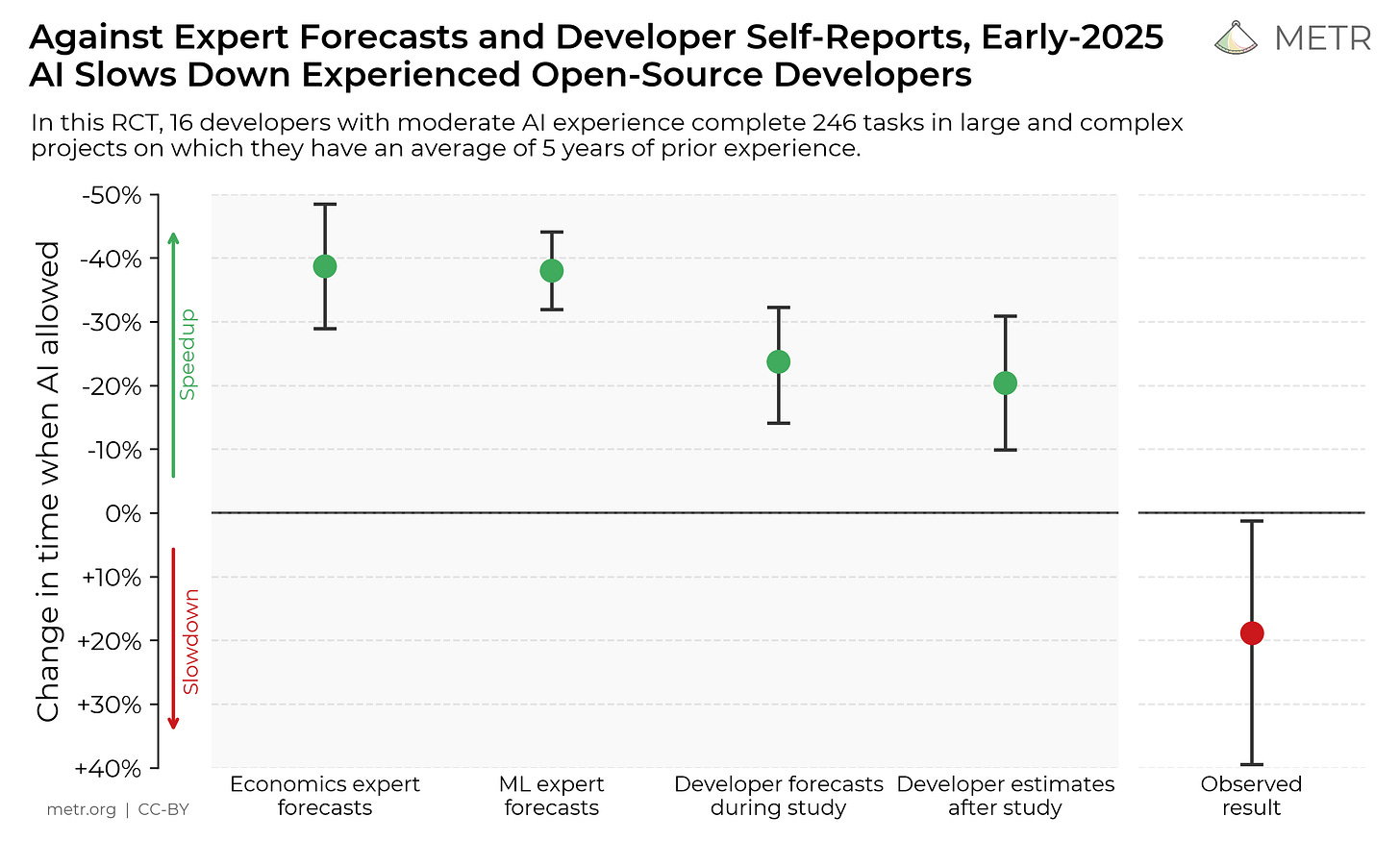

Earlier this year, METR (an AI research group) released a study on the impacts of AI1 use for developers. Prior to the experiment, they asked experts in economics and machine learning to predict how much AI tools would speed up skilled developers. They were bullish: they predicted about a 40% increase.

Developers were much more conservative: They predicted a 24% increase prior to the experiment. In assessments afterwards, they estimated that they’d actually seen a 20% improvement.

The results were surprising: developers were, in fact, about 20% slower when offered AI assistance. Most often, they would try to solve a problem using a chatbot just to get stuck “arguing” with it. If the chatbot couldn’t understand what they wanted or couldn’t offer a satisfying result, they would just continue to try to explain themselves. Meanwhile, no progress was made.

When we think about using a new tool, we think about all the problems it can solve. We don’t think about the problems it will introduce.

Plan Off the Past

It takes a lot of humility to admit that, in practice, we are rarely going to come anywhere close to the best case scenario. You will get slowed down getting out the door, and you will spend plenty of time wrestling with a tool if you’re convinced it can do your job for you. (There’s an old bit of advice I’ve heard often: if you want find the easiest way to get something done, get the laziest person you know to do it.)

Of course, the planning fallacy isn’t just about work. If you set aside an hour to read, it’s easy to see all that time disappear with only three or four pages finished. We constantly set goals with best case scenarios in mind just to see them fail.

There are two ways to solve this: either learn to account for unforeseen obstacles or learn to adapt. You can plan all you want if you’re able to figure out what problems will come up. You can stay loose with your plans if you’re willing to make changes on the fly.

Both of these demand a particular kind of reflection: you either need to remember the challenges you’ve faced or learn what adaptation means in practice. This can only come with experience and an active choice to think about that experience. Solutions don’t come along by default.

But, of course, it’s often a sort of indifference that leads to these problems in the first place. We don’t want to put in the effort needed to make any changes. If I’d faced real consequences for being late, I probably would have changed my ways a lot sooner.

We need to live attentively to replace our ideals with reality. Often, the planning fallacy is a consequence of the same indifference that leads us to automate everything that can be automated. We don’t want to think about these things—we just stick to our assumptions.

Resist that passivity. Start thinking about these things, start recognizing these obstacles, and go ahead focused on the reality instead of the ideal in your head.

I have resisted using this term, though I have not found a satisfying alternative.

I resonate with what you wrote here so much. This planning fallacy is such a universal truth, and you've explained it so insightfully. I see it all the time, especially when estimating timelines for coding projects or even just daily tasks. Thank you for putting words to this tricky human tendancy.