The Myth of Responsible AI Use

How AI will transform our working lives, and why we shouldn't let it.

(As a note: I will generally use the term large language model (LLM) instead of “artificial intelligence” (AI) throughout this article; I believe that “AI” is closer to an advertising term than a real description.)

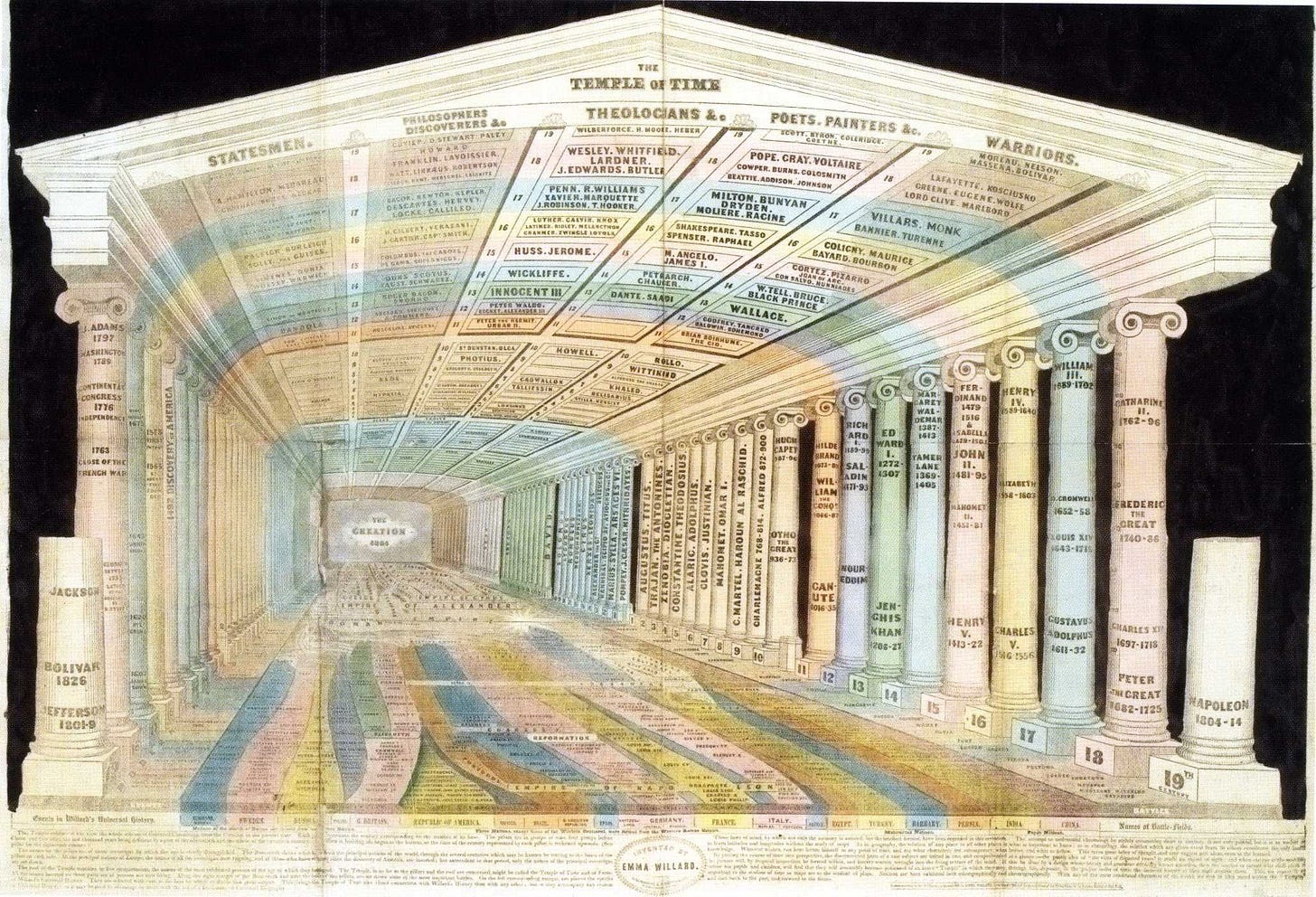

One of the many books I’ve had half-read on my desk for the past few years is Paolo Rossi’s Logic and the Art of Memory. Rossi, an Italian philosopher and historian, tells the story of the lost skills and techniques of memory. For centuries (even millennia), students learned elaborate techniques of memorization. Many learned to construct “mind palaces,” complicated mental pictures that let them create a visual image of anything they hoped to remember. Incredibly elaborate mnemonic devices helped them remember poems, facts of mathematics, scientific categories, and just about anything else.

Ancient Roman tutors charged huge fees to share these techniques. Great thinkers advocated for every aspiring student to learn the art of memory. (Though some critics argued that too much focus on memorization hurt students’ ability to reason on their own—there’s always a tradeoff, of course.) Yet despite the longstanding admiration for the masters of memory, these arts still largely faded away.

It’s not a mystery why this art disappeared. Technology made it obsolete. Printed books made it easier to rely on written record instead of these long-esteemed techniques. Searchable digital records have made it even easier to neglect the techniques of memory.

This art hasn’t disappeared altogether. I have a friend who spent years trying to build the perfect memory palace to memorize all of Paradise Lost, though he lost steam around 1,000 lines in. We still have the writings of the great memorists—there’s nothing stopping us from going back and learning the same skills they used.

But almost everyone would have the same response to this: why bother? What’s the point in spending hundreds or thousands of hours learning these techniques? Everyone easily has access to search engines that could track down any particular quote or fact you’d like in a brief moment. Even for a luddite, it’s easy enough to build a library with enough books to contain everything you could need to know. There’s simply no need for the old art of memory.

Neil Postman, an American social critic, started his book Technopoly with a similar story. His was a likely fictional account of an ancient king arguing that writing would destroy our memories. Postman used this to introduce his main argument: in a certain sense, we have become tools of our tools. The technology we use changes us: try as we might, we can’t limit it.

The inevitable end point of this culture where we are tools of our tools is the titular technopoly, a society where we entrust our tools with everything from simple everyday inconveniences to difficult moral quandaries. We no longer trust ourselves to handle these things that are really definitive of human life.

Postman released Technopoly in 1992, when he saw a frightening amount of social responsibility being handed over to computers and statistical analyses. Without a doubt, he is rolling furiously in his grave right now. The America of his time handed over things like managerial decisions, policy questions, and medical diagnoses to machines (and lost the skills that once defined these practices in the process). With the rise of large language models (LLMs for short; or “artificial intelligences” as they’re advertised), we can hand over practices that Postman would have never imagined could be automated: LLMs are commonly treated as teachers, therapists, and even religious interpreters.

I don’t think this is how most people plan to use LLMs. Nobody opened up ChatGPT for the first time assuming it would reveal a secret new religion to follow—though there are many reports of people believing exactly that. Most people I know opened it for the first time just for a bit of novelty: I remember some friends of mine all the way back in the long-forgotten year of 2022 prompting an early version of ChatGPT to write stories featuring siblings and classmates as characters. (I was in the corner refusing to participate out of an early conviction that this deserved none of my time.) We didn’t start off assuming that this would transform how we read, write, think, and believe. Still, it took over.

A recent MIT study on LLM use has shown just how much it transforms our patterns of thought. The study assigned three groups of adults an essay and gave each group a different set of research tools: the first group of students received nothing, the second group has access to Google, and the third group had access to ChatGPT.

The researchers tracked each group’s brain activity throughout the process. Unsurprisingly, the groups with no tools and access to Google showed significantly higher levels of activity than the ChatGPT group. After the essays were submitted, the ChatGPT group struggled to recall even basic points from their submissions and seemed to have internalized almost nothing. Meanwhile, the other groups maintained high activity and connection to the topic, even when offered a chance to work with ChatGPT afterwards.

The paper’s lead writer, Nataliya Kosmyna, chose to release the paper before peer review in hopes that seeing these results might discourage rampant AI use in schools and especially among children. Yet any sort of discouragement will be an uphill battle. Ohio State University recently announced their plan to mandate “AI fluency” lessons for its students. These initiatives are almost certain to continue to grow and transform more and more of our education system. Similar initiatives are taking place in the business world, where LLMs are replacing many jobs and transforming others.

These initiatives almost always claim to promote “responsible” LLM use. The stated goal isn’t to replace human workers or shift responsibility to algorithms. Yet in practice, this is always what happens. Does anyone really believe that Ohio State students will stop using AI to write their papers after taking a course telling them to use AI more frequently?

As ChatGPT and other self-proclaimed “artificial intelligences” become better and better at their jobs, it’s hard to resist using them in the workplace. As a manager, it’s difficult to hear about the possibility to automate all of your workers’ busywork and minutiae and decide to take a different path. If LLMs could just handle these time-wasting parts of the day, think of all the productive time we’d gain.

But can we really hope for this sort of responsible LLM use? If it were just a search engine or just a proofreader, it would have a good role in the workplace. But in practice, how long can this “responsible” use last?

Look back at the art of memory for a second: imagine giving a whole classroom of students pens and paper but telling them that this is only a supplement to memorization, not a replacement. You tell all of them to keep building their memory palaces and developing mnemonic devices, but they can use these writing tools as a little bit of assistance. How long would it take until the students quit memorizing and simply started writing things down?

There might be responsible ways to use LLMs. But how can we maintain that responsible use without simply giving up our work to “artificial intelligence?” A workplace isn’t a school with detention and bad grades. It’s hard to take meaningful steps to restrict LLM use, especially as it becomes harder to detect.

And, much like the art of memory, we shouldn’t expect to win our workplaces back from ChatGPT once we’ve made the sacrifice. Sure, there will still be a few sticklers who don’t want to quit reading for themselves and writing their own emails, but it’s hard to get someone to quit using a tool that takes away the hardest parts of work.

We can dream of a middle ground between avoiding LLMs entirely and sacrificing our workplaces to them entirely. But is that middle ground something we can really achieve, or is it just a fantasy used to justify handing over control of the workplace to these machines?

A friend of mine (Anthony Scholle, who’s also written on the problems of the modern workplace) wrote his high school senior thesis on the legal questions surrounding self-driving cars. He wrote this paper through the 2019-2020 school year, back when a program that could write a full essay for you still seemed like science fiction. His main question was who could possibly be held responsible for an accident caused by a self-driving car. Should we blame the manufacturer? The driver? How should we split this liability?

For as difficult of a question as this is with self-driving cars, it’s even harder with LLMs. With open-source applications that draw on literally millions of sources to find info, who’s to blame when one of these leads us down the wrong path? Whose fault is it when a manager makes a bad decision because of ChatGPT’s advice? The manager seems like the obvious answer—yet the very existence of this tool that we treat as a personal and rational being begins to complicate things significantly.

When my friend presented this paper, a teacher of ours offered a different challenge: what do we lose when we give up driving? For as difficult as it is to drive on your own, there’s still something valuable to be gained: it’s a rich source for learning how to live alongside others, especially when they’re being unfriendly and selfish

Abuse of “artificial intelligence” will without a doubt cause these same issues to an even worse degree: how difficult will it be to manage our workplaces when the responsibility for a single LLM mistake is split among managers, workers, developers, technicians, and the sources an LLM draws from? And how much will we lose when we no longer have to read, write, or research on our own?

There aren’t obvious answers to these questions—at least not satisfying ones. Any advocate of responsible LLM use has to ask how we can keep these programs as tools in the workplace instead of masters.

There’s an old New Yorker cartoon that shows a teenager, lifting weights to make himself strong and handsome. His mother rushes into the room, saying, “Honey, let me do that for you“. I’ve been sharing it in my lecture “Why We Should Not Plagiarize” for years.

Even before that handy cartoon appeared, I’d ask the question, “Would you go to a mechanic who cheated in his automotive repair classes? How about a doctor who cheated in medical school?”

(And would you vote for a commander-in-chief who avoided the military?)

Technopoly is still one of the best critiques of our technological age. In regards to the story about the invention of writing, Postman is quoting Plato's Phaedrus where Socrates tells the legend of Theuth and King Thamus.