The Everyday and the Everlasting

Lessons from Walker Percy's The Moviegoer

Most often, we learn the most important things about what it means to be human simply by observing human life. Although reason is important, it must be a supplement to experience.

Sometimes, we find the best insight into this human experience in fiction. At its best, fiction offers a picture of a small piece of human life. An author who honestly and effectively depicts human life offers us one of the most powerful tools for understanding what it really means to be human—what it is that motivates us, pains us, and defines us.

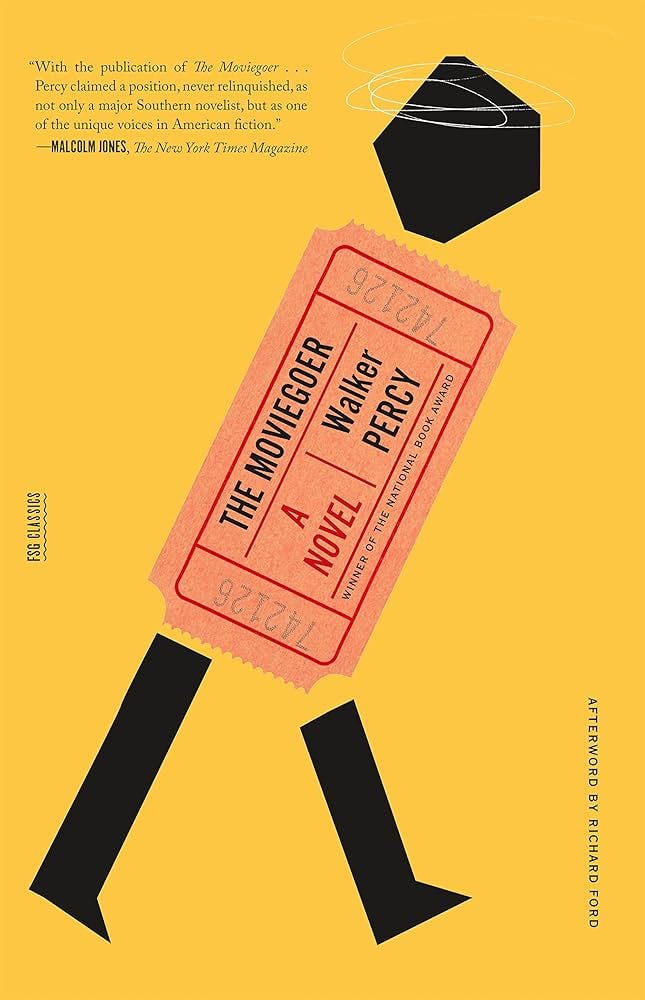

One of the best novels I’ve found that confronts these questions is Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer. The novel, set in New Orleans in the 50’s, is really an incredible reflection on just what it is that makes human life meaningful.

The protagonist, Jack, reflects often on the concept of “the search” throughout the novel. This search covers all the questions about, broadly, the meaning of life. The search is all of those questions that we need to answer to know how we should live our lives. For Jack, it’s questions about God, love, morality, and meaning.

Defining the Search

The search is intentionally a broad idea. It’s not something that we can reduce to one simple question—or, at least, not to any question that can be answered simply. We might ask, “What is the meaning of life?” but it’s not clear what kind of answer we should want from that question. If we want to find an answer, we’ll have to start by narrowing it down.

How does Walker Percy define the search? Jack says it very simply: “The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life.” If we weren’t dictated by routines and old answers for a moment, we would suddenly realize that we want to look for something more.

It’s easy to understand this feeling. It’s hard to think about these questions when we’re stuck in the routine. When we’re focused on practical questions about money or car repairs, it’s hard to take a moment to ask if we feel happy or if we know what our life as a whole is directed towards.

This is not the only thing that can stop the search, however. Jack mentions becoming engrossed in the search daydreaming about being a movie star. He imagines what it would be like to save his girlfriend from some citywide attack. It’s then that he snaps out of it and spends a minute stuck in these existential questions.

This sort of fantasizing is another obstacle to the search. When we think about a perfect world without any problems, we can’t think about the real struggles we face in life. We’re removed from what’s going on around us and become stuck in a world that doesn’t exist.

The two obstacles to the search, then, are routine and fantasy. Both of them distract us from actively thinking about these serious questions. When we’re too stuck in our routines, these questions won’t be a priority. When we’re too stuck in our fantasies, we ignore all the things that make these questions matter in the first place.

Most of the time, it’s easier to let ourselves get stuck at these obstacles. It’s not easy to take these questions head-on. How uncomfortable can it be to seriously ask yourself if what you’re doing in life is right? How difficult is it to take account of what you’re doing wrong, what you need to change, and where you are failing and succeeding?

What Starts the Search?

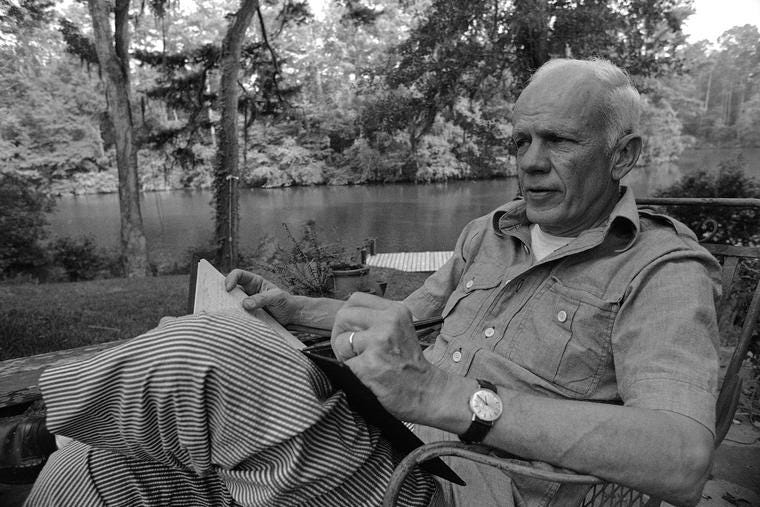

Percy’s own writing was a reflection of this search. He didn’t publish his first novel until he was 45 years old. Before that, he studied medicine and received his MD. However, he never practiced medicine. Although he planned to become a psychiatrist, a bout of tuberculosis forced him to spend most of his 20’s in a sanatorium with nothing to do but read and reflect.

For him, his sickness forced him fully out of any sort of everydayness. How could he continue on with his routine as usual? How could he live life mindlessly when every day, there was a serious risk of him losing his life? Percy even called his tuberculosis a sort of blessing: It forced him to confront these difficult questions whether he liked it or not.

Now, we can’t always rely on some extraordinary moment to come and remind us of the necessity of the search. It’s important, instead, that we find ways to get past these obstacles ourselves. We need to find a way to get away from that monotony and become fully aware of every moment of life.

Breaking away from the everydayness of life, at its simplest, means stopping the days from blending together. Routine and fantasy let us ignore the difference between the days and move through our time on autopilot. We have to begin to cultivate a constant awareness that every day is real and meaningful.

This might start simply by finding ways to remove ourselves from the predictable day-to-day routine. Something as simple as taking a new route to work, going for a walk in a part of your neighborhood you rarely go through, or cooking a meal that you’ve never tried can reawaken you and force you to pay attention to what you’re doing.

Why Are We Afraid to Dig Deeper?

There are certainly reasons we might fear the search. It’s a scary prospect to go down a path that can really force us to change. We might feel that we’re too set in our ways and fear what change could bring. We might feel that we’ve wasted too much time and won’t have the years to find the real complete answers that we’re looking for.

But really, the search only becomes more important as life continues. These questions don’t become less pressing as we get further in life. If anything, they only get more intense. The question, “What should I do with my life?” might have a simple practical answer like “Take this job” for a 22-year-old.

When these practical questions are answered, what’s left? Is there a simple, practical answer to a question like, “How can I leave a meaningful legacy behind?” Is there a quick way to solve a problem about whether you made a mistake with the path you chose in life?

It's when the search is the most difficult that it’s the most meaningful. The philosopher Rene Descartes famously wrote his Meditations at age 45 as an attempt to discard all his beliefs and start searching from the truth totally from scratch.

And, for Percy, the search never ended. Although it took him until he was 45 to finally achieve his dream of publishing a novel, he still managed to have a prolific career, working with many writers and publishing five more novels along with his nonfiction. He may have started later than some, but certainly not too late.

Even up to the weeks before his death, Percy was still deep in the search. Only a few weeks before he would die of prostate cancer, he became an oblate of a Benedictine abbey in Louisiana. The question of what he should do with his life never became less pressing and was never solved. It came to him in a new way every day of his life.

This is the last characteristic of the search: It does not have any defined end, other than the end of life. Every day presents a new question for the meaning of life—we’ll never find one single answer that resolves every question we’ll encounter.

A good searcher, then, has to remain attentive to the very end. Every day should be an opportunity to engage with these difficult questions, and we shouldn’t try to avoid them with simple fantasy or routine. It’s never too late to start the search, but we only have one life to search with. We shouldn’t waste our time avoiding the exact questions that could make us fulfilled.

What Answer Do We Want?

What’s the answer to the search? At its core, the search is centered around one fundamental question: What am I supposed to do with my life? What is the right way for me to live? Though there are many different questions that go into the search, at its core, all of these questions about God, meaning, and life seem to have a moral dimension to them. We want to know what life is meant to be.

If there is any answer, it has to be this: Vocation. Vocation at its fullest offers an answer to this question: Vocation means knowing where you belong and what you are meant for. Vocation at its fullest must be an answer to all these questions about life, both moral and practical.

The search, then, is the pursuit of vocation. It means looking for what your place in life is: Where is it that you can live how you’re meant to? Where is it that you can find a sense of belonging and purpose? What is your life meant for?

How does Jack’s search end? I think it’s best that I leave that for you to answer. If there’s one last thing to know about the search, it’s this: The answer isn’t something that you can simply be told. You can only find it if you go looking for it yourself.