Can We Choose Fulfillment Over Fun?

David Foster Wallace on the choice between fulfillment and fun.

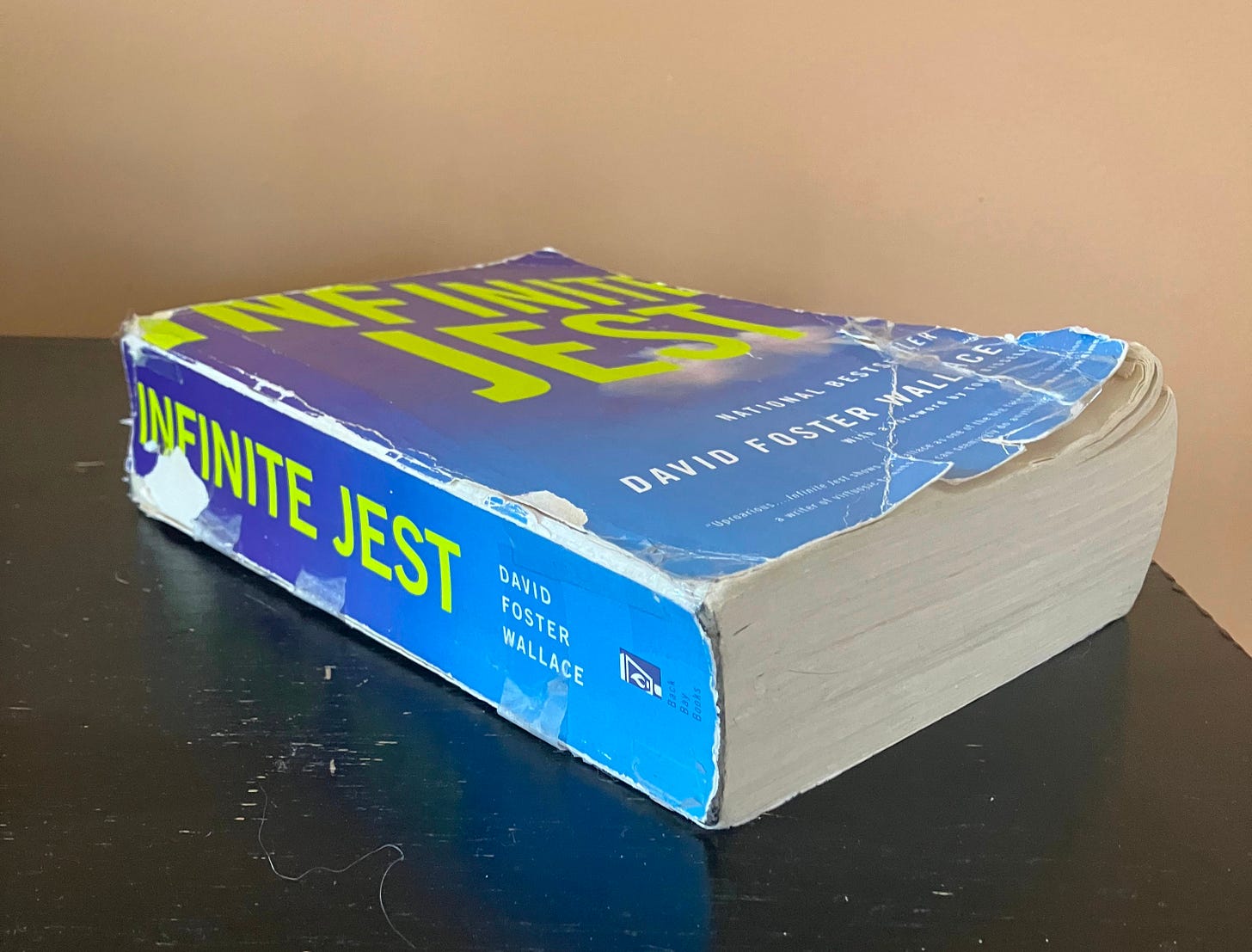

One of my New Year’s resolutions this year was to re-read David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest. We’ve mentioned Wallace a few times on The Vocation Project—speaking about the value of work and about our often unfulfilled need for a deeper sort of attention. In many ways, I think he managed to diagnose our need for purpose today better than anyone else.

Infinite Jest is the clearest example of this in his work. This gargantuan novel, 1,079 pages, was written nearly thirty years ago but still manages to capture the basic question that’s facing us today better than anything else I’ve read: Are we willing or able to sacrifice entertainment for the sake of fulfillment?

Will We Choose to Entertain Ourselves to Death?

Most of the story revolves in some way around the fictional film Infinite Jest for which the book is named. The film is so entertaining that anyone who watches it will lose all interest in living and simply view it on repeat until death. The North American government (in the book, the United States, Canada, and Mexico have all united), terrorist organizations, and a few self-interested individuals spend the story searching for a copy, hoping to use it for their own purposes.

Marathe, a double agent who’s part of a terrorist organization of Quebecois nationalists, asks a simple question: Would Americans choose to watch this movie, knowing it would mean death? Are they more interested in fun than life?

If the organization could make the film available for anyone to watch, there would be no more need for terrorism, he says. Most of America would choose to entertain themselves to death and Quebec would become independent out of necessity. For this reason, they desperately want to find the film and offer everyone the free choice to watch, knowing it will kill them.

For as pressing as this might have seemed in 1996 when the book came out, it seems so much realer today. We have the capacity to entertain ourselves to death and never be bored.

With a limitless source of entertainment available today, we’ve found our answer: The average person struggles to sacrifice any fun for the sake of purpose. It’s incredibly hard to choose something that requires patience when we have instant gratification available at all times.

There are two questions at play here: First, how can we choose something other than endless entertainment? Second, why would we choose something like that at all?

A Story of Addiction

As all these groups in the book are looking for the film, Wallace tells a parallel story: One about addiction and redemption. At a small halfway house in Boston, a few characters recovering from drug addiction find themselves looking for a way forward after hitting rock bottom. While the government agents and terrorists ask if Americans are capable of saying “no” to unlimited entertainment, these characters are left looking for a way to say “no” to something that’s already taken over their lives.

This means, at its most basic, learning to ask for help. These characters attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings where the first step is to admit that they don’t have the power to overcome addiction on their own. None of them have control over their own choices—where, then, can they turn?

What they learn is that when they lose control this way, the only thing to do is to turn control over to something else. When faced with a total loss of freedom, they have nothing to do but ask for someone else to take the wheel.

One character uses boxed cake mix as an analogy: It only works if you’re willing to follow the instructions and stop thinking you’re in charge. This, in a weird way, is freedom.

Marathe makes the same conclusion: Americans’ real problem is that they have no idea how to choose their “masters.” They choose entertainment, fun, pleasure, and simply themselves to be their ultimate guides in life. Even if they had the perfect freedom to choose, how would they decide what’s worth choosing?

Choosing Our Masters

If we think of freedom as just the ability to choose whatever we want, it’s hard to say that someone deciding to entertain themselves to death is doing anything wrong. But at an intuitive level, we know that life can’t be about simply watching something fun until you die. There needs to be something more.

Freedom isn’t just about choosing whatever we want. It’s about learning to take full use of our reason and choose what’s right, not just what’s fun. It’s about setting laws for life and choosing what we value.

Freedom must be a deliberate choice we make. Every day, we make a choice about what we’re devoted to. We choose what success means to us. We choose what rules to live by. We choose who we want to be.

Are we ready to devote ourselves to something beyond simple fun? This is not an abstract choice—this is something we face every day. In the pursuit of purpose, this might be the most difficult question we face today.

(And, for anyone curious, the book is worth reading. Every last page.)