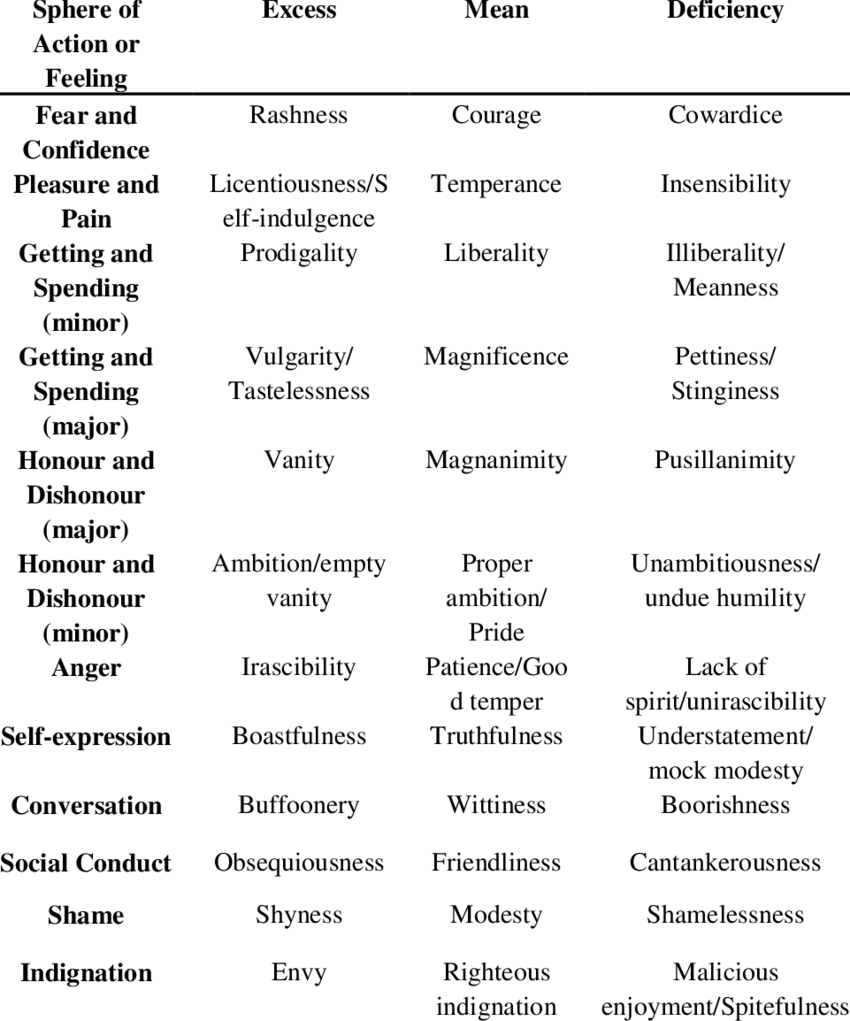

Aristotle’s list of virtues might look a bit strange today. Of his twelve virtues, some look familiar: things like courage and truthfulness are just as important to us today as they were in his time. Others might look a bit odd—things like wittiness might not seem like “virtues” in the proper sense

But the strangest thing about his list isn’t any inclusion. It’s one major exclusion: Aristotle makes no mention of humility.

Humility is nowhere to be found in Aristotle’s description. In fact, several of Aristotle’s virtues are equated with pride. “Magnanimity” (meaning “having a great soul”) is an important virtue for Aristotle. For him, this means deserving great things and knowing it—if anything, it’s demanding more for yourself. Aristotle even called pride “the crown of virtues.” For him, pride is a result of someone living well.

Our understanding is totally opposite. Pride, far from the crown of virtues, is seen as the source of all moral shortcomings—and humility is the best cure.

What’s the source of this difference? We can start to understand this by looking at what pride is meant to do for Aristotle. Pride is a matter of “honors.” By that, Aristotle means it deals with what a person deserves. Pride is the proper way to receive honors.

Every virtue has two corresponding vices: one is a kind of excess and one is a kind of lacking. For example, courage sits in the middle between cowardice and rash behavior.

A lack of pride is, in Aristotle’s mind, a lack of ambition (or too much humility). Too much pride, in contrast, means vanity. Someone without any pride thinks they deserve nothing, while someone with too much sees themselves as deserving far more than they really do.

Is Aristotle’s idea of pride the same as ours? When we think of a prideful person, we think of someone showing off and demanding that others respect their abilities. We think of someone who wants the recognition of others.

For Aristotle, this seems to be part of the equation: a proud or magnanimous person should want honor from others. But this is only part of his idea. Magnanimity and ambition mean finding what you’re capable of and seeking to live up to it. For Aristotle, this kind of pride is not demanding the honor of others but recognizing yourself for what you are.

Beyond that, real “pride” in Aristotle often manifests in acting justly towards others. Key parts of magnanimity for Aristotle are generosity, honesty, and forgiveness. Greed, lying, and grudges are beneath the real excellence of virtue.

This idea of pride seems different from our idea of the vice of pride. Really, it seems to have something in common with humility.

Humility, at its best, means seeing yourself for what you really are. This idea of pride seems to be the same—though it only seems to apply if you’ve already achieved greatness. We shouldn’t try to equate the two—it’s clear that Aristotle demands greatness and ambition that humility doesn’t require.

But this seems to offer a better conception of ambition than what we might have otherwise. Ambition doesn’t mean competing with others or trying to put yourself above everyone else. Instead, it means looking at yourself with truth and asking what you are capable of. Beyond that, it asks you to put unworthy things beneath you and strive to do good to others.

Aristotle’s idea of pride might not be the same as ours—for as much as we can still learn from him, it’s clear that our worldview differs from his. But his idea of ambition seems to show us precisely what we should hope for in life: simply what we deserve.