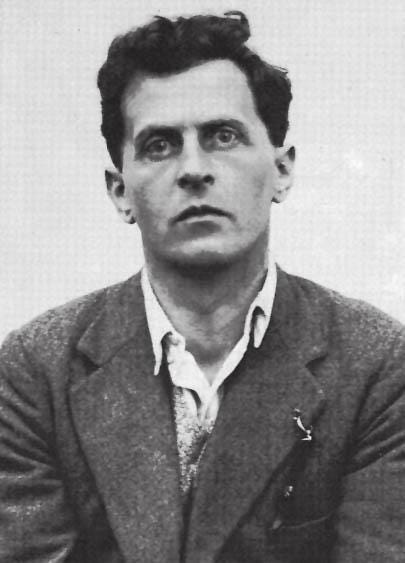

Ludwig Wittgenstein was one of the most influential philosophers in history, changing the studies of language and logic forever. But for as interesting as his work was, his character may be even more so. He was a quiet, humble man who friends often described as a “mystic.” He gave away his multi-million dollar inheritance in his 20s and chose to live as a normal Austrian, serving in the army during WWI and working as a teacher afterwards. Later, during WW2, he quit his fellowship at Cambridge University to work as a pharmacy courier in a London hospital. For as extraordinary as he was, he insisted on living in complete humility.

He was not a perfect man, of course. Famously, he would beat his students when he was a teacher—though this was normal in schools at the time, he was still often hated by his students. But Wittgenstein did do one unusual thing: a decade later, he returned to the town where he taught and tried to personally apologize to every student he’d hurt.

It’s hard for us to see him as a good man just because he apologized for beating children—yet I think it speaks to a strong sense of conscience and moral responsibility that he was willing to do so. Even though these beatings were the norm at the time, Wittgenstein still tried to make amends for what he’d done.

All of this makes it odd reading Wittgenstein’s works on ethics where he describes it as “nonsense.” How could someone who spent so much of his life trying to live morally say such a thing?

When Wittgenstein said that this sort of talk was nonsense, he of course didn’t mean that there’s no such thing as right or wrong. But he found it hard to say anything meaningful about what’s right or wrong. He struggled to find this sense in a normal description of the world: for example, he argued that you could describe every different fact about a murder without learning anything about right or wrong.

Yet there’s a feeling of meaning that we can’t escape here. Even if we can only talk about it metaphorically and indirectly, there’s something that drives us to do the right thing. Wittgenstein said that this was a supernatural feeling—not necessarily in the sense that it’s mystical or spiritual, but that it goes beyond the simple natural world.

Ethics, he argued, is not easy to define. He called it “the general enquiry into what is good.” This can mean all sorts of things: it’s not just asking what’s right to do, but also what’s beautiful or what makes a person happy.

This makes sense: he once said that ethics and aesthetics are really the same thing. Just as you can't explain in a few simple words what makes something beautiful, you can’t explain what makes something right or wrong by saying a few facts. It’s beyond description.

If there were any statement that could say what’s right, it would have to be a statement of absolute value. This means something that’s good without any qualification or reason. Wittgenstein contrasts this with relative value. Think about planning a trip: if you have a certain destination in mind, then there’s one right road that you should follow. This road is “right” relative to an arbitrary goal: if you want to get there, this will take you there.

But a statement of ethics, Wittgenstein argues, shouldn’t have an if. When we say, “You shouldn’t lie,” we don’t add, “…if you want to be a good person.” Otherwise, it’s just another relatively useful idea: if you happen to like living ethically, then don’t lie.

How can we agree on these sorts of rules for life—the things that lead to happiness, beauty, or goodness? The clear answer is that we really can’t, at least not easily. There are always things that we can argue about or things that seem particular to each person. To use Wittgenstein’s words, there’s no possible “scientific book” that could contain all these supernatural values. (Though he wrote this lecture in English, he might’ve been inspired by the German word for science, Wissenschaft—this is a broader term that can include the formal study of everything from physics to sociology to art.)

For much of his career (especially his later career), Wittgenstein argued that we waste much of our time looking for the wrong sorts of answers to our questions. We want rigorous and exact answers, but we can’t find those at all. At best, we can find metaphors, analogies, and similes.

But this doesn’t mean that there are no answers. It means that we need to look for the right answers. Instead of trying to push through dead ends, we need to turn around and take a look at things from a new view. Philosophy, he argued, is best used to get rid of the confusions we find ourselves stuck in. It’s less a matter of bringing you the answer and more about showing you the way. Wittgenstein once said that the basic form of a philosophical question is, “I don’t know my way about.”

This is a controversial position: the idea that we’re not stuck on real problems but on self-inflicted confusions is troubling to many thinkers. I’m not certain I can endorse it myself. But perhaps we need to be more comfortable with moving away from perfect answers and looking to just find our way about.