In our last article, we tried to offer a definition of happiness. There are many ways we could try to offer such a definition, but we looked at it in two particular ways: Through the objective lens of philosophy and through the subjective lens of experience.

We concluded that happiness is the one thing that every person pursues for its own sake and that it is closely linked to the experience of contentment. To be happy means to feel that your life is good as it is; complete happiness means to need nothing more than what you have.

This implies a deep relationship between need and happiness. All unhappiness, it seems, comes from some sort of unfulfilled need. Unhappiness means that you are lacking something, whatever it may be.

It’s worth investigating further to ask just what this means. What sort of needs lead to unhappiness? What can need tell us about happiness in general?

To begin, let’s ask ourselves about why we behave as we do in the pursuit of happiness. How do we identify need? How do we make decision about what’s best for us?

Why Do We Act Against Our Best Interests?

We mentioned before that it seems that every human action is aimed towards happiness. There is a natural counterargument to this: Simply, it seems that people constantly do things that make them unhappy. How can we say that people are always acting for their own happiness when it’s clear that, quite often, they don’t?

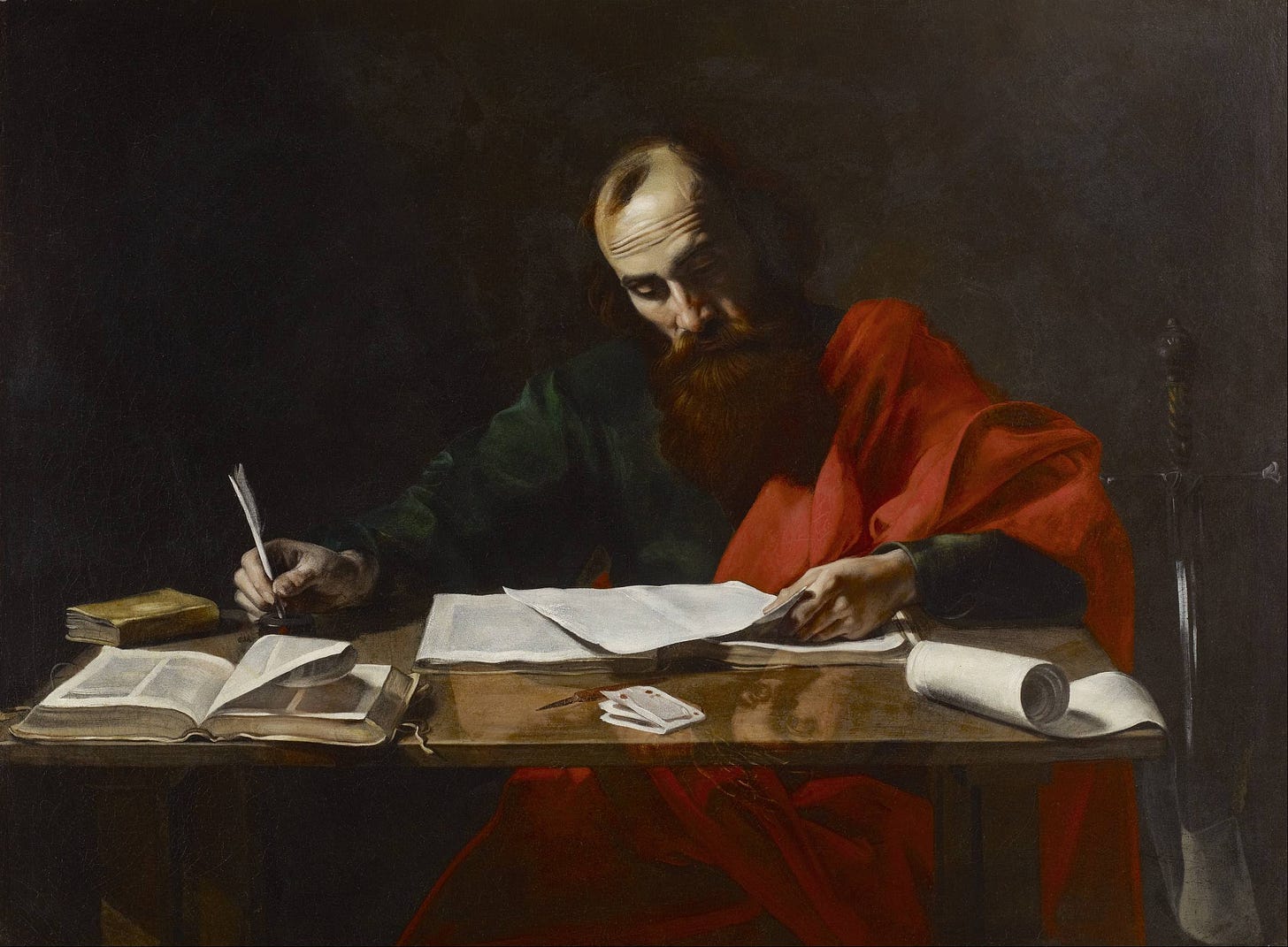

“I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate.” -St. Paul the Apostle

It’s not hard to think of times where people go against their own best interests and make themselves miserable in the process. Any quick glance at experience should tell us that people often make the wrong choice in the pursuit of happiness.

To explain this, it might be useful to turn from Aristotle to another Greek philosopher: Plato. In Plato’s dialogues, always featuring Socrates as a main character, he often dealt with the same problems Aristotle encountered. This included questions about human action and desire. Socrates often asked just why it was that people act as they do—what drives us to behave a certain way?

Plato came to a similar conclusion as Aristotle: He argued that humans are always inclined to act for the good. However, he makes an important addition to this theory: People always act for what they perceive as good. Although we have a natural inclination towards what is good, we can be misled and in turn act for the wrong reasons. Someone who incorrectly perceives what is good will, in turn, act in a way that may run counter to the good.

This is obvious in the world: There are countless examples of people who do terrible acts for the sake of what they perceive to be good. Still, it seems that in each of these cases, they believe that they are acting for what is good.

Perceptions of Happiness

We can easily apply this to Aristotle’s theory as well: We always seek happiness in our actions, but we only seek what we perceive as happiness.

Naturally, there will be many times where this judgment is incorrect. We have an imperfect knowledge of the future and an imperfect knowledge of ourselves—we can’t be certain that our actions will lead to good consequences.

Therefore, we can still reasonably say that every person is pursuing happiness by their actions even though people often act irrationally. Our desires can easily become distorted, leading to something that isn’t essential for happiness becoming an inescapable fixation.

The clearest example is something like drug addiction or another obsession, where people’s lives morph around the pursuit of a certain perceived need. In this case, something that is fundamentally unnecessary becomes a seeming necessity in life.

This does raise a significant question: If it’s the case that happiness comes from the fulfillment of needs, what is happening in these cases where someone tries to be happy by pursuing something that is obviously not a real need?

We might simply want to say that these aren’t needs and that it’s a simple illusion. But why do we constantly make these mistakes? Is it just a failure of judgment?

Where do These Mistakes About Need Come From?

Let’s look at some other examples of these seemingly mistaken needs. Think of someone addicted to eating. They feel a constant compulsion to eat more and more without any apparent end in sight. Clearly, this isn’t a real need—they could survive eating far less than they do. But where does this desire to eat like this come from?

Looking at this example, something might become clear: These false needs we’ve been talking about all seem to be based in real needs. In some way, they are distorted versions of real needs. Someone who eats too much is responding to the real need for food. Someone suffering from anxiety is likely responding to a real fear of danger; even if misguided, it’s legitimately meant as a means of self-preservation. In the case of drug addiction, these drugs often create their own dependence.

Essential and Inessential Needs

Here, we may make a distinction between essential and inessential needs. Essential needs are those things that a person needs simply by virtue of being a human person. The clearest examples of this are survival needs like food or water. However, we can also include higher order needs here, like the need for truth or justice. Although these things aren’t necessary for survival, it’s clear that they are just as innate and universal as any basic need.

Inessential needs are those needs that are acquired in the course of life. There is no innate need for any of these, but eventually, a person could become dependent on them. Addiction is the clearest example of this, though other things like luxuries or conveniences could create a sort of dependency.

Inessential needs aren’t necessarily bad. However, some detachment from them might be good. Unfulfilled desires will likely lead to unhappiness, and the simplest way to solve them is to no longer desire them. Remaining rooted in essential human needs is a good way to stay away from excess desire.

An Objective Understanding of Happiness

Earlier, it may have seemed like this theory of action was just subjective. All it could say was that people tended to act in a way that they believed would make them happy. Without an objective understanding of what people need to be happy, it seems like everyone would just have to act with an entirely arbitrary idea of what happiness is.

Now, we can see that people act from a vision of the same core needs. Things like basic needs for survival, the need for community, or the need for truth all seem to be present in everyone’s reasoning. Clearly, there are distortions and incorrect applications, but we can see something objective shared by everyone.

What Desire Can Teach Us

There’s another key thing to notice here. It may seem that desire is bad or illusory. Clearly, desire can lead us down the wrong path—it’s not always trustworthy. However, it should also be clear now that desire is a powerful guide. Desire tells us a great deal about what humans need at a basic level.

Clearly, it doesn’t always tell us the full picture. Someone obsessed with recognition and fame has a natural desire for human relationships and affection, but that original desire is now distorted and unnatural. We have to try to restore the original vision before saying anything about human nature.

With this in mind, it seems that we have to try now to look for what the most basic human needs are. What is truly sufficient for happiness? What is the least that we need to be content with life?